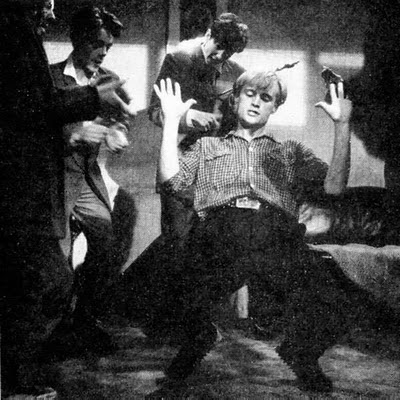

At the boy's home, his gang is having a rock'n roll party. The radiogram is going full blast, the room is full of frenzied boys.

McCallum's face grows strained. He leaves Baker in the doorway and joins the gang, who make way for him in the centre of the floor.

It looks like Violent Playground (screenplay by James Kennaway and directed by Basil Dearden) is finally going to be released on legitimate DVD, mid January 2012. I don't know whether the fact that the film culminates in a siege at a school may have delayed its release on DVD but, as might be expected from Dearden, this is not merely a sensational piece. I've written about the film in passing in some earlier posts but thought it might be worth collecting those scattered notes here - not a full-blown review, just some observations which may be of interest.

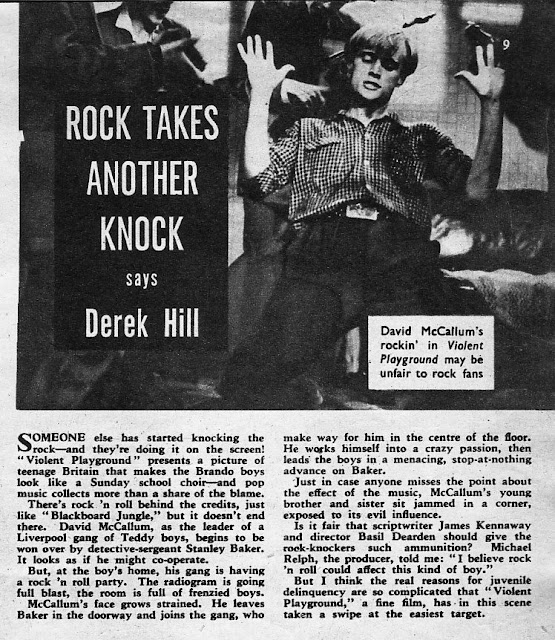

The title music, a horrible cinema-type idea of rock'n'roll, was written, incredibly, by Paddy Roberts (the South African Noel Coward to Jake Thackray's Yorkshire model), but there is, nevertheless, an extremely powerful and disturbing scene in which young David McCallum and his hoodlum friends, sans females, do a strange kind of trancelike dance to this would-be crazy beat as a gesture of defiance and contempt when Stanley Baker's juvenile liaison officer dares to enter his home.

The film, written by James Kennaway (Tunes of Glory) has elements of On the Waterfront - there's a moment where you feel McCallum's character could go either way but Peter Cushing (in the Karl Malden role, if you will) misses his opportunity - and pays pretty heavily later.

The ending, as with Jame Kennaway's screenplay for Tunes of Glory, directed by Ronald Neame, is bleak - even bleaker, you might say, than Tunes of Glory, in which Jock's crack up (superbly portrayed by Alec Guinness) at least indicates he feels the enormity of what he has done. McCallum's character in Violent Playground proves to be beyond redemption, however, so at the film's conclusion the focus shifts to saving his younger brother and sister from going the same way.

But it's that scene in which McCallum and his pals obscurely threaten lawman Stanley Baker which is the most memorable, and the fact that they do it not with knives and fisticuffs but by the simple device of surrendering absolutely to the hypnotic effect of the devil's music.

There, in a single scene, you have rock'n'roll from a terrified adult perspective: the boys do nothing, beyond swaying a little; maybe they're even so stoned (metaphorically speaking) by the music that they're incapable of violence, but that makes it more disturbing, somehow. Throughout that scene they are, to Baker's Juvenile Liaison Officer, an alien tribe, wholly unknowable, not the kind of loveable artful dodgers you can at least get some kind of a handle on. No chucklingly administered cuff on the ear will tame these demons in waiting.

It's a great cinema moment, however unfair it may be, as this article, quoted at the start of this post, suggests:

A piece on the film on the BFI's screenonline website (readable in full here) makes clear that

James Kennaway's script was inspired by an actual experiment that was carried out in Liverpool in 1949.There, a small number of policemen were rebranded Juvenile Liaison Officers and given specific responsibilities to familiarise themselves with local youth crime from the incidents themselves down to the root causes (a theory that anticipated the Labour Party's "tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime" approach unveiled over forty years later).

Interesting to note, too, the response of locals (the film is set in Liverpool) to the filming:

In order to emphasise an almost drama-documentary feel of authenticity, Dearden shot the film on location amongst the art deco tenements of Gerard Gardens, believing them to be representative of a Liverpool slum. However, his set dressers nonetheless had to exaggerate the dilapidation, and the locals later objected to the way their home had been co-opted into Dearden and Kennaway's central thesis that poverty breeds crime.

Find lots of pics from Violent Playground on the davidmccallumfansonline website here; several images above have been taken from there. The Reel Streets website, here, has then and now images of the Liverpool locations used in the film.

Below, Gerard Gardens shortly before demolition:

Original posts mentioning Violent Playground:

On Again! On Again! Or Strangers on a Train (Jake Thackray - the connection is that a Thackray-loving penfriend lived in nearby Caryl Gardens)

Gnome Thoughts ... 5 (Part of a series speculating on David Bowie's early musical influences, this mentions Paddy Roberts)

Gnome Thoughts ... 6 (David Bowie/Ken Pitt culture clash)

No comments:

Post a Comment